“This is an occasion when our hearts are filled with conflicting emotions: we are, indeed, proud to have achieved our independence, and proud that our efforts should have contributed to this happy event. But do not mistake our pride for arrogance. It is tempered by feelings of sincere gratitude to all who have shared in the task of developing Nigeria politically, socially and economically. We are grateful to the British officers whom we have known, first as masters, and then as leaders, and finally as partners, but always as friends. And there have been countless missionaries who have laboured unceasingly in the cause of education and to whom we owe many of our medical services. We are grateful also to those who have brought modern methods of banking and of commerce, and new industries. I wish to pay tribute to all of these people and to declare our everlasting admiration of their devotion to duty.” — Sir Abubakar Tafawa Balewa, KBE, PC

My Nigeria, the one that died on January 15, 1966, celebrated its independence from British rule 60 years ago, on October 1, 1960. I was six years old. We stayed in-country for another three years, with Dad working for the British, and then the Nigerian governments, charged first with administering a plebiscite in Cameroon, and then by the new Nigerian government with cleaning up leftover primordial tribal rivalries and corruption in the ancient Emirate of Kano.

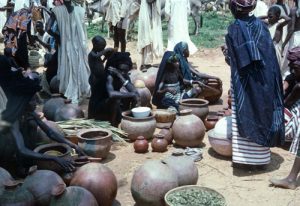

You may never have heard of the old walled city of Kano. If it’s at all familiar to you, it might be because it was featured in one of the first news stories in which the use of underage and intellectually compromised female suicide bombers came to the attention of the Western world, as they blew themselves, and dozens of others, up in Kano Market. Similar things have happened several times since, in what have become Northern Nigeria’s own Killing Fields.I loved Kano Market. My heart broke that day. For my friends For the stalls. For the vendors. For the lepers. For the Berbers. For the goats, the camels, the donkeys, the cattle. For the smells from the indigo dye pits (well, perhaps not for them). But especially, my heart broke for the vulnerable victims of the bastards who yet terrorize and often prevail. For now. I pray that it is just “for now.”

Part of that portion of my life between 1960 and 1963 involved 24-hour armed guards, and armed patrol of our compound, because the bad guys were coming for us in ways that Westerners would understand, and ways that they would not. We were under attack — on the road, in our beds, and while we were with our friends. Goats with throats slit, buried for three days, and then dug up to see if they were dead. They were not. Gagara Yasin. Poisonous snakes in the bed. Car chases. Lies, vicious tales, and implacable hatred. At one point, the rumors that my parents had been killed in the UK by the Emir’s henchmen were so prevalent that Ahmadu Bello, the Sardauna of Sokoto, contacted my grandparents and offered to adopt my sister and me. He’d already adopted me ceremonially, when I was about nine months old and newly arrived in Nigeria. I was given a Hausa name, “Hawa Numan,” after the Arabic word for “Eve” and the town in which Dad was serving as Assistant District Officer when I was born. My sister also had a Hausa name, “Nassara Mubi.” Nassara meaning “lucky,” and Mubi, the town in Cameroon Trust Territory in which she was born. We were connected. And, in Nigeria, we were at home. There are parts of Nigeria in which I would still be at home. And Muslim men I’d trust with my life, though I had never met them, because of whose daughter I am. And there are parts of Nigeria where I’d get my own throat slit without a second thought, because of whose daughter I am. I know that.

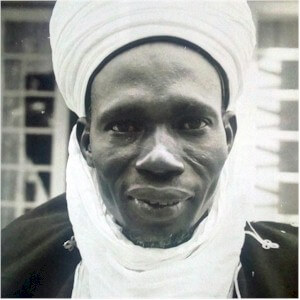

One of our dearest friends at the time was Alhaji Sir Abubakar Tafawa Balewa (ATB), the first (and so far, only) civilian elected Prime Minister of an independent Nigeria. An elegant and immensely dignified man of extraordinary intellect and gracious demeanor, it fell to him to deliver the address on Nigerian Independence Day. I reproduce it in full here, if for no other reason than to ask those reading if you can imagine such a speech, in such a circumstance, being given today. I doubt that possibility myself. But these were my father’s Muslims. These were my Muslims. (And I wish that the West would more clearly recognize that there are, still, a few of them left. I’ve been told by those who profess knowledge of covert operations in the region that the West does recognize that. And that some “top men” (h/t Indiana Jones) are paying attention to what’s going on and are assisting the good guys, as they work to expunge the evil of Boko Haram and other lunatic fundamentalists. I hope that’s true. But if it is, the progress is incredibly slow, and I don’t yet see much evidence of it myself. Just saying.Speaking of the Muslims of my childhood, I remember the faces of the women. Almost all of them were dressed modestly in brightly colored and rather normal–given their traditions and the circumstances–clothes, and had happy, smiling faces, like the ones posing in the photo at the top of this post. The Muslim women and girls of my childhood did not wear burkas or niqabs. At all. In addition, most of them had been to, or were still attending, school, and were quite literate. Not to mention the fact that almost all of them spoke two languages, Hausa and English, rather fluently.

Here, in his own words, is ATB, on October 1, 1960 (emphasis added, just to add emphasis):

Today is Independence Day. The first of October 1960 is a date to which for two years every Nigerian has been eagerly looking forward. At last, our great day has arrived, and Nigeria is now indeed an independent sovereign nation.

Words cannot adequately express my joy and pride at being the Nigerian citizen privileged to accept from Her Royal Highness these Constitutional Instruments which are the symbols of Nigeria’s Independence. It is a unique privilege which I shall remember for ever, and it gives me strength and courage as I dedicate my life to the service of our country.

This is a wonderful day, and it is all the more wonderful because we have awaited it with increasing impatience, compelled to watch one country after another overtaking us on the road when we had so nearly reached our goal. But now we have acquired our rightful status, and I feel sure that history will show that the building of our nation proceeded at the wisest pace: it has been thorough, and Nigeria now stands well- built upon firm foundations.

Today’s ceremony marks the culmination of a process which began fifteen years ago and has now reached a happy and successful conclusion. It is with justifiable pride that we claim the achievement of our Independence to be unparalleled in the annals of history. Each step of our constitutional advance has been purposefully and peacefully planned with full and open consultation, not only between representatives of all the various interests in Nigeria but in harmonious cooperation with the administering power which has today relinquished its authority.

At the time when our constitutional development entered upon its final phase, the emphasis was largely upon self-government. We, the elected representatives of the people of Nigeria, concentrated on proving that we were fully capable of managing our own affairs both internally and as a nation. However, we were not to be allowed the selfish luxury of focusing our interest on our own homes. In these days of rapid communications we cannot live in isolation, apart from the rest of the world, even if we wished to do so. All too soon it has become evident that for us Independence implies a great deal more than self-government. This great country, which has now emerged without bitterness or bloodshed, finds that she must at once be ready to deal with grave international issues.

This fact has of recent months been unhappily emphasized by the startling events which have occurred in this continent. I shall not labour the point but it would be unrealistic not to draw attention first to the awe-inspiring task confronting us at the very start of our nationhood. When this day in October 1960 was chosen for our Independence it seemed that we were destined to move with quiet dignity to place on the world stage. Recent events have changed the scene beyond recognition, so that we find ourselves today being tested to the utmost We are called upon immediately to show that our claims to responsible government are well-founded, and having been accepted as an indepedent state we must at once play an active part in maintaining the peace of the world and in preserving civilisation. I promise you, we shall not fail for want of determination.

And we come to this task better-equipped than many. For this, I pay tribute to the manner in which successive British Governments have gradually transferred the burden of responsibility to our shoulders. The assistance and unfailing encouragement which we have received from each Secretary of State for the Colonies and their intense personal interest in our development has immeasurably lightened that burden.

All our friends in the Colonial Office must today be proud of their handiwork and in the knowledge that they have helped to lay the foundations of a lasting friendship between our two nations. I have indeed every confidence that, based on the happy experience of a successful partnership, our future relations with the United Kingdom will be more cordial than ever, bound together, as we shall be in the Commonwealth, by a common allegiance to Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth, whom today we proudly acclaim as Queen of Nigeria and Head of the Commonwealth.

Time will not permit the individual mention of all those friends, many of them Nigerians, whose selfless labours have contributed to our Independence. Some have not lived to see the fulfilment of their hopes—on them be peace—but nevertheless they are remembered here, and the names of buildings and streets and roads and bridges throughout the country recall to our minds their achievements, some of them on a national scale. Others confined, perhaps, to a small area in one Division, are more humble but of equal value in the sum-total.

Today, we have with us representatives of those who have made Nigeria: Representatives of the Regional Governments, of former Central Governments, of the Missionary Societies, and of the Banking and Commercial enterprises, and members, both past and present, of the Public Service. We welcome you, and we rejoice that you have been able to come and share in our celebrations. We wish that it could have been possible for all of those whom you represent to be here today: Many, I know, will be disappointed to be absent, but if they are listening to me now, I say to them: ‘Thank you on behalf of my Thank you for your devoted service which helped build up Nigeria into a nation. Today we are reaping the harvest which you sowed, and the quality of the harvest is equaled only by our gratitude to you. May God bless you all.

This is an occasion when our hearts are filled with conflicting emotions: we are, indeed, proud to have achieved our independence, and proud that our efforts should have contributed to this happy event. But do not mistake our pride for arrogance. It is tempered by feelings of sincere gratitude to all who have shared in the task of developing Nigeria politically, socially and economically. We are grateful to the British officers whom we have known, first as masters, and then as leaders, and finally as partners, but always as friends. And there have been countless missionaries who have laboured unceasingly in the cause of education and to whom we owe many of our medical services. We are grateful also to those who have brought modern methods of banking and of commerce, and new industries. I wish to pay tribute to all of these people and to declare our everlasting admiration of their devotion to duty.

And, finally, I must express our gratitude to Her Royal Highness the Princess Alexandra of Kent for personally bringing to us these symbols of our freedom, and especially for delivering the gracious message from Her Majesty The Queen. And so, with the words ‘God Save Our Queen’, I open a new chapter in the history of Nigeria, and of the Commonwealth, and indeed of the world.

What a graceful speech. He gives thanks to the Brits (and he was talking about people like my dad). He gives thanks to the missionaries (and he was talking about Christians). He gives thanks to the private businesses (and he was talking about Western capitalists and captains of industry). He gives thanks to all of them for leading his nation forward.

At that time, Nigeria was a country of infinite promise, viewed by many (even by the then still widely-read Time Magazine, which wrote a cover story well worth reading on the subject–it’s reprinted here) as the country with the potential to lead Africa forward to prosperity and integration with the developed world.

But it was not to be.

On January 15, 1966, ATB and Ahmadu Bello, Sardauna of Sokoto, along with dozens of other senior government officials and members of their families were assassinated in a coup incited by a gang of disgruntled junior military officers, most of them from the Eastern part of the country, who resented the ascendency in the government of Muslims from the North. At least, that was the overt reason given for the overthrow. Other reasons, more political than religious, had to do with, among other things, the government’s anti-Russia/pro-UK posture, and the fact that Russia was looking for a means to install, if not a puppet government, at least one more favorably inclined to the Red Menace (plus ça change, plus c’est la même chose). Sardauna was murdered while he stood, with arms outstretched, protecting his wives (some of whom were murdered with him). I don’t know the circumstances of ATB’s murder, but his body was left by the side of the road, and parts of it were eaten. I hope by dogs. But, given the circumstances, I can’t be sure.

It was, for everyone in my immediate family, one of those snapshots in time, memorialized forever in excruciating and unforgettable detail. When it happened. Where I was. What I was doing. My mother, my sister, and I had enjoyed a rare Christmas in the UK. I’d just finished up a term at boarding school and was about to fly back to settle permanently in the States, as Dad had been offered a long-term teaching contract at a Pittsburgh university. I remember my mother sitting on the stairs, listening to radio reports of the coup and the assassinations with tears streaming down her face, her fingers twisting the ring Sardauna had given her on her first trip to Nigeria (solid silver–he ordered up a special mold, had two rings made from it, and then broke the mold himself. He wore one. She wore the other. We still have hers. I assume his was buried with him.) I remember her calling Dad (who was in the States), navigating the still complex and expensive world of international telephony to do so. And I remember how we grieved because people we thought of as part of our family, people we thought of as dear brothers and beloved uncles, had been foully and traitorously murdered.

Later that year, after something resembling order had been restored (but it never was, really, ever again–and the West bears much of the responsibility for that), Dad was the first, and perhaps still, the only Westerner to be allowed inside Sardauna’s tomb. He finally got the chance to say goodbye to his old friend, who’d refused to come and see us off when we left Nigeria for the last time in 1963. He refused to say “goodbye,” because he was sure, he said, that “we’d come back.” If we had gone back (Dad was in two minds about a proposed position as senior liaison officer between Lagos and Whitehall), I expect we’d all have died in the coup, too. Dad and Sardauna kept in touch until the end–the last missive we received from the second-most revered Muslim leader in the old Sokoto Caliphate was a card he sent to us in December of 1965, wishing us all a Merry Christmas, signed in his customary green ink. Two weeks later, he was dead. And, as the oldest child, the only one with clear memories, although they are childish memories, of the place and of the kind, humorous and affectionate man I remember, I still mourn his loss.*

*Before we left Nigeria, Sardauna gave Dad two gifts, with strict instructions as to what was to be done with each upon Dad’s death. One was a very beautiful silver-plated hammered brass coffee tray, about 24″ in diameter. The other was an elephant’s tusk, carved out to represent the crocodile pulling The Elephant’s Child into its mouth, the elephant’s child resisting, and his trunk forming and stretching out as they battled in a tug-of-war.

Sure enough, when Dad died, and his will was read, he had carried out Sardauna’s wish to the letter. I have the tray. My sister has the tusk. The tray hangs, today, at the half-way point of my stairs. (Funny, that. I’ve just remembered that the elephant’s tusk sat half way up the stairs in our home in England for years. History may not always repeat, but it almost always rhymes.)

**Parts of this post were contained in one I wrote a couple of years ago. Thanks for indulging me.

Published in GeneralThanks for reading Created with Sketch. Quote of the Day: But Always as Friends - Ricochet.com. Please share...!

0 Comment for "Created with Sketch. Quote of the Day: But Always as Friends - Ricochet.com"