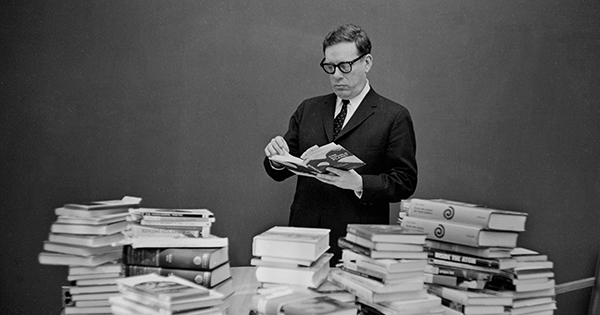

This year marks the 100th anniversary of the birth of Isaac Asimov (Hon.’80) (1920-1992), Boston University’s most prolific faculty member (he was a BU professor of biochemistry). In a world that values and rewards hedgehogs, he was the ultimate fox: his more than 500 books span almost the entire Dewey Decimal System. When I joined the BU faculty in 1998, I half expected to see a building, a lecture hall, a square, even only a bench, named after him, but if there is such a spot, I have yet to discover it. It gratifies me that his personal papers are archived at BU’s Howard Gotlieb Archival Research Center.

Asimov is of course best known for his science fiction, and among his numerous short stories and novels, the Foundation series, whose first three books I read more than half a century ago as a teenager, stands out. Set tens of thousands of years in the future, the series is based on the premise that human civilization, as embodied by an empire that spans our entire Milky Way, is falling apart. One man, the psycho-historian Hari Seldon, has devised a scientific method for not only predicting the future, but also influencing its unfolding in such a way as will restore civilization, this time carried by a decentralized galactic polity.

As I sit at home and read pundits’ attempts to imagine the post-corona world with its empty office buildings, half-deserted campuses, bankrupt businesses, interrupted supply lines, closed cultural venues, struggling artists, resentful blue-collar workers, and exacerbated socioeconomic inequalities both within and across countries, and as I ponder arguments that ascribe the sheer scale of our problems to globalization gone too far, I am reminded of Hari Seldon. He thought salvation lay in undoing what he might have called “galacticization,” but his plan did not pan out. Obviously, the great 20th-century philosopher Karl Popper’s refutation of the idea that the future can be predicted did not survive the millennia into Hari Seldon’s time. The current pandemic is a case in point for Popper’s insight. Who could have predicted, for instance, that last March the production of the long-awaited Foundation TV series—set to air on Apple TV+ next year—would have to be suspended due to COVID-19?

Intriguing as the Foundation series may be, it is another set of novels that I find eerily reminiscent of my own life in confinement. In The Caves of Steel and The Naked Sun, Asimov depicts an overpopulated Earth in which people live under Spartan conditions in overcrowded domed cities. Some humans, called “Spacers,” have colonized nearby planets, where, cared for and served by robots, they live out their very long lives on huge estates, either alone or with only their spouse for company. Spacers are taught from birth to avoid personal contact. Face-to-face interactions, which Asimov calls “seeing,” and especially procreation, are considered repugnant. Communication is through what he calls “viewing,” a two-way teleconference that allows the participants to hear and see each other. A few Spacers live on Earth, but they cannot mingle with the general population as they have very weak immune systems, there being no pathogens on their planets. When it is necessary to interact with the inhabitants of Earth, Spacers wear nose filters and gloves. By the same token, Earth people are required to undergo body sterilization before entering the Spacers’ enclave. Their wealth, conceit, aloofness, and longevity make them targets of resentment by the general population.

As I compare my relative comfort to the distress of all those who do not receive a monthly paycheck, cannot work from home, or live in quarters so cramped that social distancing is impossible, I cannot help noticing the parallels between my here and now and the bifurcated society depicted in Asimov’s two dystopian novels. Will those angry people who protest on the streets against confinement measures one day turn their resentment against people like me? If so, what form will it take? I hope the analogy ends here, for in Asimov’s universe, the Spacers eventually die out.

In scientific circles, Asimov is most remembered for his Three Laws of Robotics, formulated to ensure that robots would never harm humans. As part of Boston University’s new AI Research Initiative, ethical concerns need to be addressed.

This might provide an appropriate setting for naming a feature of the campus after Isaac Asimov on the centenary of his birth.

“POV” is an opinion page that provides timely commentaries from students, faculty, and staff on a variety of issues: on-campus, local, state, national, or international. Anyone interested in submitting a piece, which should be about 700 words long, should contact John O’Rourke at orourkej@bu.edu. BU Today reserves the right to reject or edit submissions. The views expressed are solely those of the author and are not intended to represent the views of Boston University.

Explore Related Topics:

Thanks for reading POV: Why Isaac Asimov's Novels Still Speak to Us Today, 100 Years after His Birth - BU Today. Please share...!

0 Comment for "POV: Why Isaac Asimov's Novels Still Speak to Us Today, 100 Years after His Birth - BU Today"