Julien Neaves

– courtesy Maria Nunes

In a week and a half, Tobago-born Toronto-based poet, essayist, novelist, and playwright M NourbeSe Philip was awarded a prestigious Canadian cultural prize and saw her 2008 book Zong! win a literature magazine poll.

On July 7 the Canada Council for the Arts Molson Prize winners were announced: Philip in the arts category and psychologist and mental health researcher Gordon J G Asmundson in the social sciences and humanity category. The council awards two Molson prizes of Can$50,000 to distinguished Canadians in these fields annually.

The prize is funded by a $1 million endowment given to the council by the Molson Family Foundation and encourages recipients to continue contributing to the cultural and intellectual life of Canada.

On June 28 literature magazine World Literature Today (WLT) announced Philip’s book Zong!, a book-length poem about the murder of Africans on board a slave ship in 1781 for financial gain, won the 21 Books for the 21st Century Readers’ Poll. Earlier this year WLT editors invited 21 writers to nominate a single book, published since the year 2000, that has had a major influence on their own work, along with a brief statement explaining their choice. WLT published the longlist and then invited readers to vote on their favourites and Zong! was the winner.

Newsday interviewed Philip about Zong! recently.

The Zong Massacre

Philip learned about the case that inspired it years ago when she read Black Ivory: A History of British Slavery by English historian James Walvin. It mentioned an incident with a slave ship in 1781 coming across the Atlantic: the journey took longer than normal because the captain had never captained before.

“It got lost and essentially came close to Tobago, but its destination was Jamaica, so it was really off-course.”

During the voyage, water ran low and some of the people on board, both crew and enslaved Africans, became ill and died. The captain decided to throw overboard around 150 enslaved Africans.

“The number tends to be slippery, but about 130 to 150 (were) killed so he could ensure there was more water left for those who remained on board.”

Philip said her research indicated the ship left the coast of Ghana with 470 enslaved Africans. She noted at that time an enslaved person was insured as “cargo,” just as property is insured today, and at that time insurance law said if an enslaved person died during the normal course of events, the owner could not collect insurance money for them. However, if there was a rebellion or a revolt and the enslaved person was killed, the owner could make an insurance claim.

Philip said from the documents she read it appeared the captain and his associates feared there would be a revolt on the ship because there was not enough water,and came to the conclusion to throw some 130-150 people overboard in three separate groups.

The vessel ended up on the south coast of Jamaica, the slaves presumably sold to slave owners there, and returned to Liverpool. Then the owners of the ship, two relatives named Gregson, made a claim against the insurance company for “destruction of property.”

“The very people they murdered, they now make a claim against the insurance company for that.”

The company, owned by the Gilbert brothers, refused, not because the slaves were human beings, but because they disputed whether the Gregsons had the right to destroy “property.”

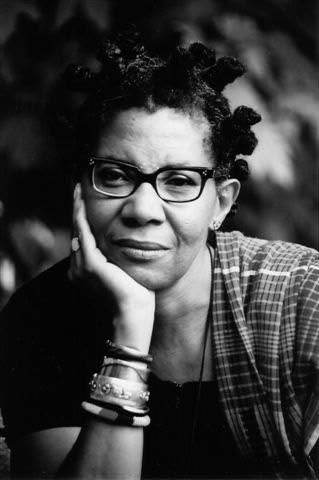

Philip won the $50,000 Canada Council for the Arts Molson Prize in the arts category which was announced on July 7. – courtesy Maria Nunes

In the first hearing of Gregson vs Gilbert the court ruled in favour of the shipowners against the company. During the case, the idea of murder was raised by one of the lawyers, but the judges ruled it was not murder but a case of “destruction of property.”

The company appealed, and at that hearing, the fact that it rained during the voyage and the crew would have been able to collect water to give to the enslaved people came up. The appeal was heard by Chief Justice Lord Mansfield, who made a lot of rulings related to slavery. Mansfield ruled in favour of the insurance company and ordered a new trial.

“After that, the trail goes cold. There does not appear to be a new trial. And the shipowner died.”

Philip noted, however, the case became very significant to abolitionists organising against the slave trade and slavery.

She explained the name of the ship was originally Zorg, a Dutch word meaning “care,” which would become “morbidly and macabrely ironic,” given what happened. When the ship was repurposed on the African island of São Tomé and when it was repainted the “r” became an “n,” changing the name to Zong. The event would become known as the Zong massacre.

‘Unauthoring’ Zong!

American writer Philip Metres who nominated Zong! for the WLT poll, described it as “at once a brilliant documentary long poem and a sort of ritual exorcism of the demons of the slave trade.

“Philip’s visionary use of the burying language of law to recover the shreds of the voices of the lost is stark, elemental, and electrifying. It is poetry raised to the level of a truth commission. This work has launched a thousand poetic justice projects in the mode of documentary recovery.”

Asked about her approach to Zong! Philip explained she used to practise law and visited the law library where the case was reported.

“I opened the book and it was a two-page case report. And I remember I was really stunned. Two pages? How do you condense the horrific murder of 150 people into two pages?”

She explained in her study of law she had to read a lot of cases and as cases “move up the ladder” it is an extractive process and the “messy human factors” are squeezed out.

“The issue of law is often very narrow.”

Philip recalled thinking that in this two-page document were locked away all the stories aboard the Zong and she set about looking at various ways of using the legal document to try and find those stories.

“In the first stage, I was locked in the document as the slaves were locked in the hold of the slave ship.”

She explained in the first section the only words she used to make her poems were the ones found in the document, which was a little over 500 words long.

Then two years later she had the idea of breaking the words up and “find words inside words”, a process she compared to the word game Boggle. She made dictionaries in which she listed all the words in the documents and found words from them. For example, from “Lord Mansfield” she could extract “man”, “field”, “fled”, and “name.”

“And then using only those words then the poem began to create itself.”

The sections have Latin names for bone, salt, wind, reason, iron, and then “Ebora,” the West African word for underwater spirits. The book ends with the Latin “notanda” or “that which must be noted,” which is a prose section in which she talked about the process of the book.

Philip pointed out the cover of the book features her name and the phrase “as told to the author by Setaey Adamu Boateng.”

Who is Setaey Adamu Boateng?

She explained that each name has a personal meaning to her, but it is no one person or being.

“There is a sense in which I ‘unauthored’ the book. A sense the story was given to me by the ancestors (and) the name stands in for that idea of my stepping aside to let the voices come through.”

She recalled it was very important for her as part of the process at some point to “seek permission to bring these voices forward.” She visited Ghana and consulted with a priest.

She stated in the notanda that it “is a story that can’t be told yet it must be told.”

“We can never know what happened onboard the ship or know the whole story.

“Also the horror of it. How do you tell horror? Atrocity?

“But then we must tell it. The only way it can be told is through untelling it or not telling it – putting the ego out of commission. The story is telling itself.”

She pointed out the words are all over the page, almost as if floating on the water.

“You could read from beginning to end, or from top to bottom. Like water moving on the ocean, bobbing and moving around. I am kind of giving over to the reader. Let the reader make sense or nonsense of what is going on.”

The true prize

On the Molson Prize, Philip said someone approached her who knew her work and wanted to nominate her. She learned about the win a couple of weeks ago.

“I am pleased. Very, very pleased. There is a financial aspect, which is always nice (and) as a poet and writer who is unimbedded (not in the university system), artists often aren’t phenomenally wealthy.”

On the WLT win, Philip said there was no money attached but she was “very joyful” people chose Zong! as it was about people knowing about the events. She said she was deeply humbled and heartened that people would want to learn about them.

“It helps us to move on and become better people. Being human is hard. We are trying to live up to the best we are capable of.

“The thing that makes me happiest is if more people will hear about the work and read about it and more of our people, all people. Everyone needs to know this.”

She pointed out 1781 was a time of agitation and upheaval (the slave trade drawing to an end, the American, French and Haitian revolutions) and was similar to what was happening today with the George Floyd uprising.

She added that it was lovely that it happened on the 240th anniversary of the event.

“We are trying to break through still. We still have not. We have not broken (through) to a place of ideals where many of us hold the view that everyone should be treated with dignity and respect. Have adequate housing, jobs and healthcare. It is so important and still far away for many people. And it is getting worse with climate change and people fleeing lands.”

Philip said she always bears in mind that in today’s societies racism is still very much present.

“We have to keep our eyes on that.

“I very much want for us as humankind and as African-descended people (to) understand that ‘I am’ must be sufficient. The fact that we exist must be sufficient. It cannot be contingent on whether we are black, white, pale, gay, straight, this class or that class, Hindu, Muslim, or Christian. We are human. ‘I am.'”

She said she had worked hard for several years and her work spans poetry, fiction and drama.

“I took from the Caribbean the idea of being engaged as a member of society.”

She has written about racism, sexism and homophobia.

“If the prize helps to expose more people to the work and they go on to read other black writers, then it is worth it.

“Prizes are wonderful. But I have never written because of prizes. They help pay a few bills, but it’s not the driving force in my life.”

Asked about her Tobago roots, Philip said she was born in Tobago and then came to Trinidad at eight, attending Bishop Anstey High School.

“Both of my parents’ families are from Tobago (but) both islands reside in me. I have a particular love for the island of Tobago and it is my rock and refuge. It is the place I write from even if I am not writing about it.”

She returns home to TT every year except last year and she has been trying to make her way back.

“Tobago is my home, and Trinidad.”

Philip said she also sees herself as a “Caribbean person.”

“So the prize is not just for me; it is a prize for Tobago, and Trinidad, and the Caribbean.

“We Caribbean people always punch above our weight, no matter where we are. And the prize is also for the ancestors who allowed us to be here.

“And we come from societies with the Caribbean as a beginning. It is something we can be proud of, and we have produced wonderful people. And we are from Africa, the cradle of humanity. It is a marvellous continent in spite of all of the ills. It is important to pay the prize forward. Really important.”

And what is Philip currently working on? She replied that it was “several things” including a lot of work she started years ago. She is writing a couple of plays, some poetry, and immediately working on some writing during the pandemic which she is hoping comes out next year.

NourbeSe Philip at a glance

Although primarily a poet, NourbeSe Philip also writes both fiction and non-fiction. She has published three books of poetry, Thorns – l980, Salmon Courage – 1983 and She Tries Her Tongue; Her Silence Softly Breaks – 1988.

She has received Canada Council awards, numerous Ontario Arts Council grants and a Toronto Arts Council award in l989.

In l988 Philip won the prestigious Casa de las Americas prize for the manuscript version of her book She Tries Her Tongue… She is also the l988 first prize winner of the Tradewinds Collective prize (TT) in both the poetry and the short story categories.

Her first novel, Harriet’s Daughter, was published in l988.

Her second novel, Looking For Livingstone: An Odyssey of Silence, was published in l991. In l994, her short story, Stop Frame was awarded the Lawrence Foundation Award by the journal, Prairie Schooner.

(Source: https://ift.tt/36XCHQj)

Tobago-born M NourbeSe Philip wins Can$50,000 arts prize Source link Tobago-born M NourbeSe Philip wins Can$50,000 arts prize

Thanks for reading Tobago-born M NourbeSe Philip wins Can$50,000 arts prize - Illinoisnewstoday.com. Please share...!

0 Comment for "Tobago-born M NourbeSe Philip wins Can$50,000 arts prize - Illinoisnewstoday.com"